- Home

- M. LaVora Perry

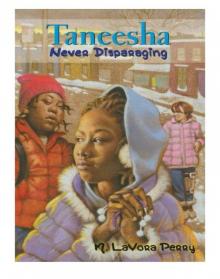

Taneesha Never Disparaging

Taneesha Never Disparaging Read online

Table of Contents

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER 1 - GUARANTEED PUBLIC HUMILIATION

CHAPTER 2 - THE “I’ M-NOT-RUNNING-FOR-ANY-DANG-THING” PLAN

CHAPTER 3 - BONKED ON THE HEAD

CHAPTER 4 - BLOODY & BEATEN ON BERNARD

CHAPTER 5 - SHOWTIME AT THE BEY-ROSS’

CHAPTER 6 - E.T. MEETS SIX X-RAY EYES

CHAPTER 7 - NO PARENTS HOME

CHAPTER 8 - THEY HAD BEEN TO HELL

CHAPTER 9 - SONG OF AN OLD FRIEND

CHAPTER 10 - HUMAN-EATING BIGFOOT

CHAPTER 11 - FLOUNCING OUT

CHAPTER 12 - DOWNRIGHT DANGEROUS FLORIDA

CHAPTER 13 - GAGGING UP GUAVA-MANGO JUICE

CHAPTER 14 - THE MEAN LAUGH

CHAPTER 15 - DRESSED LIKE A CANDIDATE

CHAPTER 16 - SNAKE SNACK

CHAPTER 17 - INVISIBLE, COZY BLANKET

CHAPTER 18 - STANDING O

Acknowledgements

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT WISDOM PUBLICATIONS

THE WISDOM TRUST

Copyright Page

Praise for TANEESHA NEVER DISPARAGING

“A FAST-PACED portrait of a girl grounded in her Buddhist practice and loving family, coping with the daily struggles of growing up.”

—Kathe Koja, author of Buddha Boy

“Taneesha’s voice is FRESH, FUNNY, and TRUE as a lotus blossom in a muddy pond. Readers will become familiar with Nichiren Buddhism—and the word disparaging—as Taneesha navigates her way through fifth grade as a Buddhist, daughter, and good friend to all.”

—Kelly Easton, author of Hiroshima Dreams

“A JOY TO READ. This book addresses the issues many kids face today with a fresh and positive perspective. Don’t miss this beautifully and skillfully written novel.”

—David Richardson, columnist for Reading Today

“I will definitely use this as a ‘BOOK OF THE MONTH’ IN MY CLASSROOM. I can hardly wait for the next installment!”

—Magnolia Walker, reading teacher (4th and 5th Grades), Crawford County Elementary School in Roberta, Georgia

“INSPIRATIONAL and highly recommended.”

—Midwest Book Review (on Taneesha’s Treasures of the Heart)

To my husband, Cedric Richardson, and my parents, Mattie and Rudolph Perry, for always supporting and believing in my dreams; to my children, Nia, Jarod, and Jahci for calling Taneesha out to play; and to every reader who has stood by this girl from day one—thank you.

CHAPTER 1

GUARANTEED PUBLIC HUMILIATION

There I was, scribbling Taneesha Bey-Ross, a Monday, January 7, 2008, across the top of a fresh page in my writing notebook, without a clue that chaos was just minutes away. I looked through a classroom window at the freezing outside—cloudy, like it was all the time lately, with snow on the ground and everything. But you’d never have known it in Room 509 of North Cleveland’s Jane Hunter Elementary School. Toasty. Just the way I like it. So toasty that even though I’d forgotten to wear a sweater, I stayed warm in my “dress-code” get-up—white blouse, navy blue pants, black shoes.

I looked around at the astronomy sculptures, geometry mobiles, and A and B+ papers that decorated the walls, shelves, and ceiling. With a leg stretched out, I silently bounced a rubber heel on the blue-grey carpet, the kind for inside and outside, and breathed in its new-car smell. Glad to be back in 509.

It was the first day of school after Winter Break and I’d actually wanted to get back to Hunter. The break had been getting boring. Nothing to do.

So there I sat, scribbling with one hand and tangling the fingers of the other in the nappy tip of one of my twisty African locks.

“And so, fifth graders—” Trim Mr. Alvarez, who had the exact same tan as the oat flakes I’d had for breakfast over three hours ago, pointed to the list of words he’d written on the chalkboard:

“These are just some character traits that good leaders possess. Keep them in mind when you consider who to nominate for class officers in our coming election.”

I couldn’t help thinking how Mr. Alvarez was always so sharp. Today his short, coal-black hair looked especially shiny. Like he’d Vaselined it up or something. Neatly combed, of course. He had on this crisp, beige shirt, a dark blue necktie and matching suit pants. The crease in his pants could have sliced a hunk of cold cheddar cheese.

For some reason, the more I stared at Mr. Alvarez’s crisp, beige shirt, the more I thought of whole grain wafers.

My stomach gave a long growl. I quickly swept my eyes around the room and saw Rayshaun Parker, a hefty kid, look at me and then look away, bored. Good. That would have been all I needed—Rayshaun catching me growling. It seemed like he hadn’t heard my stomach. Nobody else seemed to either. Thank goodness.

Now that Rayshaun was in my head, he parked his irritating self there. Great. Mainly, that boy and I only talked to each other when we had to. You would have never known we used to be best friends back in the day, in kindergarten.

See, one time, back then, Rayshaun and I were playing House together in the little kitchen area in our classroom. He was the daddy and I was the mommy. Rayshaun was clobbering a baby doll’s back over his shoulder, “burping” it. It was one of those dolls whose hair is really just molded plastic.

He picked that particular doll for our “daughter” because he said her skin looked like the chocolate outside of an ice-cream sandwich just like mine. He said that since she was just a baby it didn’t matter that she didn’t have cornrow braids or lips like me (she basically had no lips; I have plenty). Our “son” was always this little white doll that looked more like Rayshaun—just without his nappy hair.

The whole “family” thing was all Rayshaun’s idea, not mine, since he wanted to marry me and I wasn’t sure I felt the same way about him. But I liked to play House though.

So there he was, pounding our poor daughter’s back, while I stood at the ironing board ironing a red-and-white cotton bandana—the kind farmers and gang members wear. The iron wasn’t hot or anything, of course. It didn’t even have a plug.

All of a sudden, Rayshaun stopped whopping that doll, looked straight at me, and said, “Taneesha Bey-Ross, my mother says you going to hell because you ain’t Christian.”

Rayshaun’s hair wasn’t black like most kids’. It was this dusty brown like somebody had dumped a bucket of sand over it and he’d shook it off—only some stayed.

When he told me I was going to hell, I’d felt like he’d dumped dirt all over me. But I couldn’t shake it off. I didn’t let him know I felt that way, though.

After school that day, I stood in my kitchen and cried, “Mama, why’d you tell?!”

The week before, my mother had come to my class for Cultural Traditions Day. She brought food like other parents did—collard greens. She talked about how African American slaves ate them back in the day and how collards were healthy because they had a lot of fiber and more calcium than a cup of milk. All the kids kept saying her greens tasted good and that we looked just alike, except I was a pretzel stick and she had a shape.

But Alima Ross couldn’t leave it at that. Oh, no, not my mother. True to form, she had to go all extreme and tell everybody about our family’s unique little tradition.

“Mama, why’d you tell we’re Buddhist?!” I’d screamed in the kitchen. “Rayshaun said his mother says I’m going to hell!”

Mama had had on a nurse’s uniform—a scrub top and pants—that was pinkish red like grapes. She stooped down and made her dark brown face even with mine. I smelled apples in the grayish afro puff on her head. With a white ball of Kleenex in her hand, she started w

iping away the tears and snot that ran down my face.

“Taneesha,” she said, “I’m so sorry Rayshaun said that to you. But sweetie, hell and heaven aren’t places. They’re right in here.” She patted my chest. “Buddhahood is too. Do you know what that is?”

I sniffed and shook my head. I thought Mama might have told me what Buddhahood was before but I couldn’t remember.

“It’s happiness that’s as big as the whole universe. And when you chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, you make it come out.”

She told me to chant for Rayshaun and his mother to be happy.

Mama and I chanted together at the altar in our living room and that made me feel okay.

Oh, the simple mind of a kindergartner. I’d actually thought that would be it. Chant and the world would go back to normal.

But what really happened was this: For a long time—on the school playground, in the lunchroom, standing in line, whenever and wherever he could—Rayshaun, who was chubby back then, not solid like he is now, kept following behind me, saying “You going to hell, Taneesha. You better get saved.”

I never told our teacher. I was afraid if the other kids found out what Rayshaun said, they’d agree with him.

And I didn’t say anything more to Mama about it either. Even when she asked. I just acted like it was all over.

Why’d I do that? For one thing, her chanting idea had obviously been a big fat dud. For another, I didn’t want her coming up to Hunter to talk to Rayshaun because then my whole class would have definitely found out about the whole situation.

So I’d just whisper back at that boy, “No I’m not going to hell, Rayshaun Parker. Hell’s not a place, it’s inside.”

After a while, he stopped bugging me. But we never went back to being friends like before. Far from it. Whenever Rayshaun got the chance, he’d laugh at something dumb I did.

Guaranteed public humiliation: one more reason why what was coming next in Room 509 was totally out of the question.

I glanced at the clock. I wondered how long we had ’til lunch. I imagined chowing down on a cool slice of cheese laid out on a piece of Mr. Alvarez’s crunchy shirt.

“Now, let’s get started on the task at hand,” he said, looking mighty cheesy. “Are there any nominations for class president?”

CARLI FLANAGAN, YOU STOP THAT RIGHT NOW!

A terrifying sight ripped me from my cheddary daydream—Carli’s hand shooting up into the air. I wanted to scream at that girl flat out, instead of only in my suddenly splittingheadachy head.

I would have screamed, too, if it weren’t for the fact that I’d have looked crazy.

I had a sick feeling about that puny, pale hand, all dotted with brown freckles. It was my best friend Carli’s hand, a hand that was eleven years old—just like mine. That hand flapped wildly over Carli’s wavy, red hair. With each flap, she wriggled in her seat so much that the metal brace on her left leg clunked against the metal of her desk’s leg. But she didn’t even notice the clunking. She was too busy flapping.

“Psssst!” I whispered, “Carli! Carli!” as loudly as I could without drawing Mr. Alvarez’s attention. I hoped with everything I had that Carli wouldn’t do what I thought she would if I didn’t stop her in time.

Desperate, I started going: “Nam Myoho Renge Kyo! Nam Myoho Renge Kyo! Nam Myoho Renge Kyo!...” like a chanting machine.

I bet my parents would have loved knowing I was doing that—even if it was just silently.

Hmmph. As if I’d sit up in class chanting out loud.

But maybe I should have. Because my way didn’t work.

Next thing I knew, I heard Carli saying, “I nominate Taneesha Bey-Ross for president!” Pudgy, caramel-brown Kendra Adams seconded the nomination. And that was that.

Once the whole class saw me get nominated, I was too embarrassed to say I wouldn’t run.

Don’t worry. You won’ t win anyway. Losers never do.

For once, I actually hoped Evella was right. She’s my evil twin—totally imaginary but a major butt-pain anyway. I nicknamed her Evella a while back. Anyway, I hoped she was right—not about me being a loser, of course, but about me not winning. I didn’t want to be class president. It was hard enough just being me.

Trapped in my seat, all I could do was tangle my fingers in the tip of one of my locks. And cook up an escape plan.

CHAPTER 2

THE “I’ M-NOT-RUNNING-FOR-ANY-DANG-THING” PLAN

After school, in the cloudy daylight, I walked up Bernard Avenue with Carli, who was just a little shorter and meatier than me. We had to walk because we weren’t eligible to ride a school bus since our parents had signed us up to go to Hunter even though both of us lived closer to other schools. We were bundled in our puffy winter coats—mine was the silvery-purple one I’d gotten in November when, thanks to global warming, the weather had just started getting cooler. Carli’s coat was pink. We both had on scarves, gloves, and boots. I wore earmuffs and an extra pair of socks. I hate Jack Frost nipping at my nose so I don’t take chances.

I couldn’t wait to make it to Rosebush Road—a street lined on both sides with mini-mansions that this rich guy named John D. Rockefeller built in the 1900s. Walking, I remembered Mama saying our red-brick house—the tiniest one on Rosebush—was just the right size for our family.

Carli and I walked on packed, dirty, days-old snow that hid parts of milk cartons, broken glass bottles, and pieces of crumpled McDonald’s french-fry holders. We passed houses—some rickety or boarded up, others in okay shape, some looking good. Covered in snow, even the worst ones looked better than usual. Before we’d get to my house, we’d walk ten blocks and cross Aristotle Avenue—U.S. Route 20, just a few miles south of Lake Erie.

It’s uphill from Bernard to Rosebush. But you don’t really feel it so much when you’re walking, only when you’re riding a bike and pedaling against gravity—a bike like the beautiful magenta one I’d gotten over the summer, when it was warm and sunny, and I was just plain old Taneesha, not anybody’s candidate.

While I mentally hammered out the details of my I’m-not-running-for-any-dang-thing plan, I looked at all the traffic crossing Aristotle two blocks ahead of us. Aristotle, a main roadway, was in the middle of a major upgrade that included a wider street and new sidewalks, street signs, and bus shelters. I remembered my father saying Aristotle ran east and west from Massachusetts to Oregon.

“Taneesha,” Carli said, interrupting my thought-flow, “for your campaign, I was thinking I could ask my aunt Bridgid to make some of her candy. It’s always a big hit at the bazaars they have at her church. We could pass it out with ‘Taneesha’s the Sweetest!’ buttons. What do you think?”

Why, I wondered, was Carli asking for my opinion now? It was a little late for that, wasn’t it? Since she’d already up and nominated me.

“Candy sounds nice.”

You are such a wimp.

Just what I needed—Evella’s expert opinion.

“Watch it, shrimp!”

I looked up. Standing right in the middle of the sidewalk—not on one side or the other, which would have been the courteous, human thing to do—stood an ogre.

Her face was like a broad, brown crayon with eyes. A swarm of poisonous spikes, skinny extension braids, poked from underneath her knitted skullcap. It was blood red, just like her bulging jacket—a jacket that bulked up a body that seemed more than big enough already. Black backpack straps cut into the red of her jacket. Dark blue slacks clung to her thick legs. And, like bulletproof armor, long, wide army boots covered the two tanks that almost passed for feet.

“I’m talking to you. And you, too, white girl.”

Do you think she needed to say it twice?

Like the Red Sea in that cartoon movie, The Prince of Egypt, Carli parted to one side and I swerved to the other.

We went back to walking up Bernard—slower than I wanted to, considering how the Beasty One had just barked at us. But I had to creep along so Carli could keep up since she ha

d that metal brace on her left leg and limped a little.

Neither of us talked about what had just happened. Probably, like me, Carli wanted to be out of that girl’s hearing range.

“Some people,” she whispered when we made it to the corner of Aristotle and Bernard.

“Yeah,” I said, with absolutely no feeling. “Some people.”

I wasn’t really thinking about the girl anymore. I’d gone back to tinkering with my I’m-not-running plan. I hadn’t been able to really focus on it in school because there were too many distractions—math, science, lunch, all that stuff. But now the plan was taking shape—and yanking my parents’ strings was a big part of it.

Had I known better, instead of wasting all my brain cells on the nomination, which was nothing compared to what was coming, I would have been thinking up ways to get the heck out of Dodge before that big brown ogre—Shrek untamed—landed on me.

“She’s probably from Legacy,” Carli said.

“Hunh?”

“That girl. She’s probably from Legacy Middle School. You know how teenagers always think they’re all that.”

“Oh. Yeah. Right.”

“Why so quiet?”

Carli and I had just crossed over to the south side of Aristotle and I couldn’t bring myself to tell her what I was really thinking: “Girl, are you nuts?! My life is careening down Disaster Street because you nominated me!”

“Oh. No reason. Just thinking.” I wasn’t totally lying. I didn’t have time for chit-chat. I needed to put the final touches on my plan to reverse the damage Carli had done. “I’m just ready to get home, that’s all.”

“Nam Myoho Renge Kyo. Nam Myoho Renge Kyo. Nam Myoho Renge Kyo.”

At the start of dinner, Mama, Daddy, and I finished doing Sansho together, chanting three times. We sat at our oak kitchen table with four yellow walls around us.

Taneesha Never Disparaging

Taneesha Never Disparaging